The 2005 Nobel Peace Prize:

A Report from Oslo

By Irwin Abrams & Scott London

The Nobel Peace Prize for 2005 was awarded jointly to the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) and its director general Mohamed ElBaradei for their efforts to control the spread of nuclear weapons and promote peaceful applications of nuclear technologies. On October 7, 2005, the Norwegian Nobel Committee announced that Mohamed ElBaradei and the IAEA deserved recognition for addressing one of the greatest dangers facing global security. "At a time when the threat of nuclear arms is again increasing, the Norwegian Nobel Committee wishes to underline that this threat must be met through the broadest possible international cooperation," Chairman Ole Danbolt Mjøs said at the press conference held at the Nobel Institute. "This principle finds its clearest expression today in the work of the IAEA and its director general."

Mohamed ElBaradei had been nominated for the Peace Prize a number of times and was reported in the press as a leading contender in both 2004 and 2005. Many observers saw the award as a vindication for the IAEA chief after his handling of weapons inspections in Iraq in the days leading up to the American-led invasion in 2003. The Bush administration had insisted that Saddam Hussein harbored a secret nuclear weapons program and called on IAEA's observers to confirm that suspicion. But after hundreds of inspections, ElBaradei and his team found no unconventional weapons and no evidence of a nuclear weapons program in Iraq. Apparently outraged by this, Washington mounted a campaign to block ElBaradei from a third term as the agency's director general. In spite of these efforts, ElBaradei was able to gather widespread international support and beat back the administration's efforts. In October, just a month into his new term, he and his agency learned they had won the Nobel Peace Prize.

Mohamed ElBaradei had been nominated for the Peace Prize a number of times and was reported in the press as a leading contender in both 2004 and 2005. Many observers saw the award as a vindication for the IAEA chief after his handling of weapons inspections in Iraq in the days leading up to the American-led invasion in 2003. The Bush administration had insisted that Saddam Hussein harbored a secret nuclear weapons program and called on IAEA's observers to confirm that suspicion. But after hundreds of inspections, ElBaradei and his team found no unconventional weapons and no evidence of a nuclear weapons program in Iraq. Apparently outraged by this, Washington mounted a campaign to block ElBaradei from a third term as the agency's director general. In spite of these efforts, ElBaradei was able to gather widespread international support and beat back the administration's efforts. In October, just a month into his new term, he and his agency learned they had won the Nobel Peace Prize.

The award to ElBaradei and the IAEA was the latest in a series of prizes honoring champions of nuclear disarmament. Earlier prizes had gone to such laureates as Linus Pauling (1962), Eisaku Sato (1974), and Alva Myrdal and Alfonso García Robles (1982). In 1975, Andrei Sakharov received the prize in part for his nuclear disarmament work in the Soviet Union. In 1985, the award was given to the International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War. And in 1995 physicist Joseph Rotblat and the Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Affairs were honored for their efforts to eliminate nuclear weapons.

Some observers were quick to seize on the fact that the Nobel Committee had recognized people or organizations fighting the spread of nuclear weapons at regular ten-year intervals since 1975. Two months before the prize was announced, the news agency Reuters had predicted that the 2005 award would again focus on non-proliferation efforts, citing what it called "a once-a-decade trend." It certainly seemed fitting that the Nobel Committee should focus on the issue that year. It was the sixtieth anniversary of the bombings on Hiroshima and Nagasaki toward the end of World War II where more than 200,000 people lost their lives, most of them innocent civilians. But much of it was idle speculation. Chairman Mjøs brushed aside the idea when pressed by reporters, and Geir Lundestad, secretary of the Committee and director of the Nobel Institute, called it a sheer coincidence. "There is no pattern," he said simply.

Some observers were quick to seize on the fact that the Nobel Committee had recognized people or organizations fighting the spread of nuclear weapons at regular ten-year intervals since 1975. Two months before the prize was announced, the news agency Reuters had predicted that the 2005 award would again focus on non-proliferation efforts, citing what it called "a once-a-decade trend." It certainly seemed fitting that the Nobel Committee should focus on the issue that year. It was the sixtieth anniversary of the bombings on Hiroshima and Nagasaki toward the end of World War II where more than 200,000 people lost their lives, most of them innocent civilians. But much of it was idle speculation. Chairman Mjøs brushed aside the idea when pressed by reporters, and Geir Lundestad, secretary of the Committee and director of the Nobel Institute, called it a sheer coincidence. "There is no pattern," he said simply.

In his presentation speech at the December award ceremony, Chairman Mjøs made reference to this presumed trend. "It has been claimed that every tenth year the Norwegian Nobel Committee awards the prize to someone seeking the abolition of nuclear weapons," he acknowledged. "It is difficult for the Committee to deny the charge." But such awards have been given more frequently than once every ten years, he pointed out. "And it was not the case in 2005 that the Committee had zeroed in on this field in advance. It would be truer to say that when the Committee, after a long discussion of this year's 199 candidates, finally selected the IAEA and ElBaradei, we came to the realization that once again the prize was to go to someone who favors reducing the importance of nuclear arms in international politics.

In the address, Mjøs praised the IAEA for its skilful handling of the Iraqi weapons inspections and for its critical work of monitoring clandestine nuclear activities in such trouble spots as Iran and North Korea. Mjøs described ElBaradei as the "central figure" in the emergence of the IAEA as a rigorously independent and objective watchdog agency, an organization that exemplifies the need for high levels of international cooperation in keeping the world safe from nuclear weapons. While the prize was "very much a tribute to Mohamed ElBaradei in person," Mjøs said, he hastened to add that it was also meant "to recognize the 2,300 staff from 90 countries who currently work for the IAEA, as well as the many who worked there before."

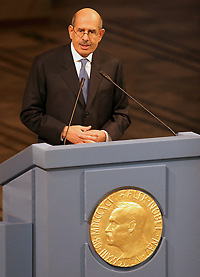

Following the speech, Mjøs presented the Nobel Peace Prize medal and diploma to Mohamed ElBaradei and Yukiya Amano, chair of the IAEA's governing board and the agency's official representative at the proceedings. The King, Queen and Crown Prince of Norway, along with about 1,000 invited guests, rose to honor the laureates after the formal presentation. The renowned American cellist Yo-Yo Ma then performed a suite by Bach.

ElBaradei's 25-minute Nobel lecture ranged widely and discussed the issue of nuclear disarmament and non-proliferation against a broader canvas of global challenges. Like poverty, infectious disease, organized crime, and the depletion of natural resources, he stated that the problem of nuclear weapons transcends borders and cannot be solved without sustained, multinational cooperation. There were three primary dimensions of the problem that needed attention, he said: the rise of an extensive black market for nuclear material and equipment, the spread of nuclear weapons and other sensitive technologies, and the failure of disarmament efforts on the part of existing nuclear-weapons states.

ElBaradei's 25-minute Nobel lecture ranged widely and discussed the issue of nuclear disarmament and non-proliferation against a broader canvas of global challenges. Like poverty, infectious disease, organized crime, and the depletion of natural resources, he stated that the problem of nuclear weapons transcends borders and cannot be solved without sustained, multinational cooperation. There were three primary dimensions of the problem that needed attention, he said: the rise of an extensive black market for nuclear material and equipment, the spread of nuclear weapons and other sensitive technologies, and the failure of disarmament efforts on the part of existing nuclear-weapons states.

ElBaradei stressed the importance of keeping nuclear weapons from spreading to rogue states or falling into the hands of extremist groups. But he also emphasized the need for established nuclear powers to make sharper reductions in their Cold War arsenals. There were still some 27,000 nuclear warheads in existence, he pointed out, most of them in the United States and the former Soviet Union. He said it was "incomprehensible" that a decade and a half after the end of the Cold War, the major nuclear-weapons states still operated with their arsenals on hair-trigger alert.

He went on to outline several concrete steps that could be taken immediately toward reducing those stockpiles — actions which, if taken, would also help establish the sort of international consensus needed to strengthen the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty. But such steps would not be enough on their own, he added. "The hard part is: how do we create an environment in which nuclear weapons — like slavery or genocide — are regarded as a taboo and a historical anomaly?"

ElBaradei concluded on a sober yet hopeful note. After the Berlin Wall fell, he said, many hoped that a new world would emerge, one that was equitable, inclusive, and interconnected. "But today we are nowhere near that goal." Walls dividing the East from the West have been torn down, but we have yet to build bridges between the North and the South, between the rich and the poor.

"Imagine what would happen if the nations of the world spent as much on development as on building the machines of war," he said. "Imagine a world where we would settle our differences through diplomacy and dialogue and not through bombs or bullets. Imagine if the only nuclear weapons remaining were the relics in our museums. Imagine the legacy we could leave to our children. Imagine that such a world is within our grasp."

This article was adapted from the book, Nobel Lectures in Peace, 2001-2005, edited by Irwin Abrams and Scott London (published by World Scientific, 2009). Photos by Scott London.